this dysphoria is over a month old!

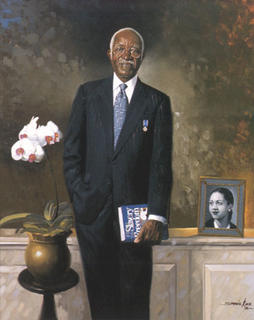

(And yet, I'm posting it anyway...) I spent a great deal of time watching television this weekend, in between reading proofs of the new John Hope Franklin memoir coming out. The television consisted of horrifying scenes accompanied by dischordantly upbeat reports from New Orleans and the pastel hothouse of the US Open, all of which I watched with a weird hollow urgency in my chest. And then I'd be reminded of my work by the high pitch of the chemical smell floating up from the blues in my lap, and I'd go back to reading what was an inspiring and impressive story. John Hope Franklin has survived a century's worth of racism in this country, filled his life with work and teaching (by virtue of the assistance and bottomless sacrifices made by his wife Aurelia, featured in the frame to his left). His book read like an extended and extremely impressive resumé dotted with brief anecdotes. Several patterns extended themselves from Franklin's quiet and optimistic text to the distracted reader.

(And yet, I'm posting it anyway...) I spent a great deal of time watching television this weekend, in between reading proofs of the new John Hope Franklin memoir coming out. The television consisted of horrifying scenes accompanied by dischordantly upbeat reports from New Orleans and the pastel hothouse of the US Open, all of which I watched with a weird hollow urgency in my chest. And then I'd be reminded of my work by the high pitch of the chemical smell floating up from the blues in my lap, and I'd go back to reading what was an inspiring and impressive story. John Hope Franklin has survived a century's worth of racism in this country, filled his life with work and teaching (by virtue of the assistance and bottomless sacrifices made by his wife Aurelia, featured in the frame to his left). His book read like an extended and extremely impressive resumé dotted with brief anecdotes. Several patterns extended themselves from Franklin's quiet and optimistic text to the distracted reader.John Hope Franklin did everything absolutely by the book, with the righteous and powerful exception of his refusal to bow to the expectations of the racist nation in which he was born. A rough paraphrase of the mantra that thrums in his mind when faced with the cruelest, most manipulative and intimidating of racial injustices is You must do as they do, but do it a thousand times better. The second repetition which manifested itself: Franklin started his life believing in the U.S. government, and continues to from the looks of his memoir. Despite being misused and manipulated by presidential adminstrations and their minions responsible for addressing the very injustices they were calling on him to enumerate, he soldiers on to the next civic task, ever optimistic about the democratic and academic institutions to which he's dedicated himself.

My sense of his anger was mute, the emotion being tempered, I believe, by his vast historical perspective. But then I think his life has been spent trying to demonstrate the significance of history, the truths contained in it. The limitless potential in its study for people to gain the capacity to evaluate, question, recognize (reknow), and empower themselves.

P.S. The NYTimes magazine's delightful and disastrous Deborah Solomon interviewed him shortly after the book's release.

Q. As a renowned scholar of African-American history, a field that some say you virtually invented, how do you think Hurricane Katrina has altered our view of race in this country?

The tragedy is that Katrina changed our view at all. We should have known the things that Katrina brought out.

Like the fact that blacks in New Orleans live in the lowest and most flood-prone elevations, while whites occupy the higher and safer land?

Yes, but we don't have any interest in that. We have more interest in who won the last football game, and who won the last basketball game, and who's on TV, and who's in Hollywood. It's a fundamental problem of this country today, the lack of critical thinking and judgment on the part of

the American citizens.

Lawrence F. Kaplan just published an essay in which he laments the decline of national greatness not among our leaders but among our citizens, among ordinary Americans who have lost all sense of civic responsibility.

It was never any different. It has been the same since 1619. That was when the first ships arrived from West Africa with blacks on them. We got off to a bad start right then!

How can you, as a man who was born in Oklahoma at a time when lynchings were common, and who later worked with Thurgood Marshall on Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark case that outlawed segregation in public schools, claim that we have made no progress in advancing the rights of African-Americans?

I'm not saying that! I'd jump out the window if I thought we had made no progress. What I am saying is that the changes have been superficial, and we are still a segregated society when it comes to schools and the neighborhoods where we live.

And of course, you are a teacher yourself. In fact, you are said to be the most decorated professor in this country. I hear you have so far earned 130 honorary degrees.

I think it's up to 137. But that's not the way you measure anything. Some of it is conscience pay. I don't want to belabor the point, but giving out awards makes the givers feel good. It is easier to give me an honorary degree than to make certain that all blacks have a decent place to live.

You yourself live rather nicely in Durham, N.C., where you're a professor emeritus at Duke University and have a building on the campus named after you.

I call myself retired now, and I try to act my age.

How, exactly, does one act at 90 years old?

You go fly-fishing all day.

Or you write all day. Your history of a slave family, "In Search of the Promised Land," just came out, and next month you're publishing your autobiography, "Mirror to America." Do you ever get tired of working?

I have never experienced fatigue the way other people do. I remember the first time I experienced

fatigue. It was in 1960, and I was in Australia. I thought I was going to die.

Now that you are a widower, who prepares your meals for you?

His name is John Hope Franklin.

Yes, I've heard of him. How's his cooking?

Pretty good. I had a big cookout on Labor Day. I had six people over for dinner. I did Hawaiian chicken, and baby back ribs, and we had corn on the cob, and potato salad, which I am ashamed to say that I did not make myself but bought at Harris Teeter supermarket. Isn't that awful?

Unforgivable. Have you ever missed a day of work?

No. For what?

What do you think about before you fall asleep at night?

I don't think about the past much. And I never think about whether I am going to wake up or not the next morning. I'm too busy trying to read the last pages of the newspaper before it falls in my face.